Mae La, a refugee camp directly on the border of Thailand and Burma, is filled with roofs made of metal and organizational difficulties. Mae La is mostly dirt, and the roads change seemly randomly from wide enough for one car to pass, to foot paths, then motorcycle paths, and then back to roads. The soil is not strong enough to grow anything, there is no sewage system, and all drinking water is brought in by NGOs. Mae La is roughly 1.9 miles long and is the home of approximately 41,000 refugees. Its full length runs along a main road. On the Thai side, there is a road and a meager fence with randomly stationed military; on the Burmese side there are only mountains. Because of its location by the road, Mae La is able to have power and phone service, a luxury most Burmese refugee camps in Thailand do not have, which allows some schools to use computers a few times a week. For this reason, “Mae La is different than most refugee camps.” Salinee Tavaranan, the director of the Border Green Energy Team (BGET), told me. Having electricity, phone service and the internet is a great advantage for people who otherwise have few opportunities, jobs, or activities. In my talk with both Salinee and the students, I learned that for a child in the camp, there are only three options after completing school: find a job with an NGO in the camp, apply to a school in Thailand and hope for acceptance, or apply for the resettlement process which is long and has decreased its operations since 2008. The odds for a better future increase with education and vocational skills, thus Mae La’s access to electricity is invaluable.

At Mae La, BGET is involved with a school called Engineering Study Program (ESP). At ESP, approximately 40 students over the age of 18 learn skills like: Photoshop, English, calculus, engine mechanics, welding, and Autocad (CAD software). I asked Salinee what skills were the greatest benefit for these students and her response was that job-related skills were the most valuable, “…That is why we train them [the refugees] in more practical knowledge, like how to use biogas systems. The hope is that the students will be hired by an NGO to educate others on how to use the systems they have learned about.” ESP is a three year program and is slowly expanding its offerings as funding permits: a library has been added, as well as a larger work place. When asked if there was something BGET could do to help, Mula, a student at ESP, responded, “I do not know what to say, I think it is up to Thai government.” Many Karen refugees within the camp are taking advantage of all the opportunities offered to them and accelerating at all of them, but despite the refugees’ efforts, in the camps of Thailand, it is the Thai government’s policies and decisions that determine the future of these 41,000 people.

Mula, a 20 year old refugee living in (and unable to leave) the Mae La camp, sat down with us for an hour and told us her story. Mula is tall, has long straight black hair, and a beautiful smile that seems to always be present on her face, “My name is Mula Le Bray; my name means perfect hope.” I have never met anyone who deserves this name more than Mula. She is learning English and says shyly, “I only speak a little.” Yet she is able to have a conversation on any topic. When she does not understand she smiles, stares directly at me and says, “I do not understand.”

In Burma, villages near Mula’s village were burnt to the ground, but hers luckily was not entered. As a result, Mula’s three brothers went to Mae La to find jobs teaching. “Mae La camp is out of the [Burmese] government’s control” Mula explains, so her family was notified that refusal to bring her brothers back to Burma would result in their arrest. Consequently, three days after Mula’s final high school exams, her family left their home, drove one day to the border of Thailand, and then walked another day to Mae La refugee camp where they have now lived for almost 5 years confined within the mountains and fence that outline Mae La.

Burmese refugees cannot leave Mae La camp because they do not have identification. Many refugees do not have a Burmese ID and very few have a United Nations refugee ID. As a result, the refugees are stuck in limbo: they do not want to return to Burma due to the risk of violence, but it is illegal for them to enter Thailand without an ID. Although there is military presence, security of Mae La is not strict, fences in some places can be walked over. What keeps the people in is the fear of being deported or possibly killed; the refugees have escaped one difficulty only to emerge into another. They are stuck, detained at the border they thought they’d be crossing.

As a result, Mula continues to live in Mae La with her three brothers, mother, and father. Her father is the pastor at the neighboring church. I asked Mula if she is happy in the camp and she replied, “Yes, real happy… I see a lot of my people and I am very happy to live with them.” The community, Mula says, helps each other, “if we need something our neighbor will help us and we help them.” However, despite her positivity Mae La camp is still a refugee camp and the people recognize they are not free. Mula explains, “[in Mae La] I can not do what I like, because it is not our land and we live in control of Thai government.” In the camp the “power is turned off at 9 pm and turned on 5 or 6 am.” Monthly rations are rice, chilies, charcoal, salt and sugar, and Mula states, “they give but not enough.” Many people eat only two meals a day.

Despite the rough life of Mae La camp, there are some opportunities and Mula is taking full advantage of them. Mula is a third year student at Higher Education for Engineering. During exams this year she helped tutor many of her fellow students. Mula is committed to her studies and remains positive and compassionate. When we asked her what she would like to be when she gets older she replied, “I will be a teacher.”

When asked about what she thought of her past, Mula said simply, “There are a lot of sad stories in camp… I think my story is not the worst…” What I was sad to learn, is that Mula is right. After talking to her, I spoke to another student named Hsereh. Hsereh is from the Papu district in Burma within the Karen state. Mula and others told me this is one of the most dangerous districts of Burma. Hsereh came to Thailand by himself, “because I want to get higher education.” The opportunity to go to school in Mae La is actually much greater than in Burma where costs are very high and there are many discriminatory procedures. Hsereh’s parents “allowed me to go,” so he and some of his friends walked one day into Thailand. His parents have not joined him; he remains the only member of his family to choose to become a refugee. Hsereh is in Thailand alone because his family, like many people, does not want to leave their home. “Especially my parents,” Hsereh says, “she, [his mom], doesn’t want to stay in the camp, because they doesn’t want to leave their village, because she has a garden and a field.”

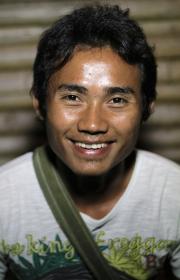

Hsereh lives in Mae La O a much smaller camp deep in remote jungle, but he studies at a 4 year leadership school at Mae La. In addition, for at least one more month, he is a teacher at the Blessed Children Home which is where I met him wearing a Bob Marley shirt, acid washed jeans, and a gold tooth accenting his smile like an exclamation point. Hsereh’s experience is quite different than Mula’s. Potentially for lack family at the camp, Hsereh tends to take more risks. I asked Hsereh if anyone has helped when he has needed something. He replied, “yeah, yeah, but when I was student, I meet many many many difficulties, because I don’t have like pocket money. Sometimes I want to eat like a bread but I don’t have money.” So he and some of his classmates, during their two-week school holiday, sneak from the camp at night to find work in northern Thailand. The security is not the strictest but the punishment for being caught sneaking in or out of camp varies from deportation to being shot at.

A picture of Hsereh.

Just as Mula answered easily and quickly when asked her future plans, so did Hsereh. “I want to serve my nation, community and society.” Although he is hopeful, he is aware of the binds holding him and he finished by saying, “But I can do nothing at this time, because I don’t have anything so I can’t do anything for my people.” Hsereh is doing what he can to learn and help his people, but once he finishes school the apparent opportunities will become scarce. Nonetheless, Hsereh remains hopeful. I told him how sad and frustrating his story is he said, “It is ok, everything is ok.”

Mula and Hsereh’s stories are not uncommon. They are not the only people I talked to who have plans for the future; they are not the only people who told me they will help their people. All of the refugees seem to share their drive and compassion. Although, Salinee pointed out that not many of the youth are joining the fight in Burma, many of them are hoping for peace while learning other ways to help their people. The youth of Mae La refugee camp may only know of the Burmese abuse of power that has put them where they are, but they do not accept it. The Karen youth are educating themselves and setting high but attainable goals for themselves. Faced with injustice from their home country and a seemly dismal unpredictable future, the Karen remain positive and focused on anything that could improve their lives.

What would you do if you were them? What will you do for them?

This post is written by Simon Wolf.